By Ellen Wilkinson

The Royal Opera House’s Dante Project, which premiered in October 2021 is a tour de force of creative collaboration. Intricate and angular choreography from Wayne McGregor (the Royal Ballet’s resident choreographer since 2006) fuses with Tomas Adès’s ambitious new score and striking set design by artist Tacita Dean in this retelling of Dante’s epic journey through the realms of the afterlife. The role of Dante is the swansong of the Royal Ballet principal Edward Watson, whose remarkable career with the company has spanned twenty-six years.

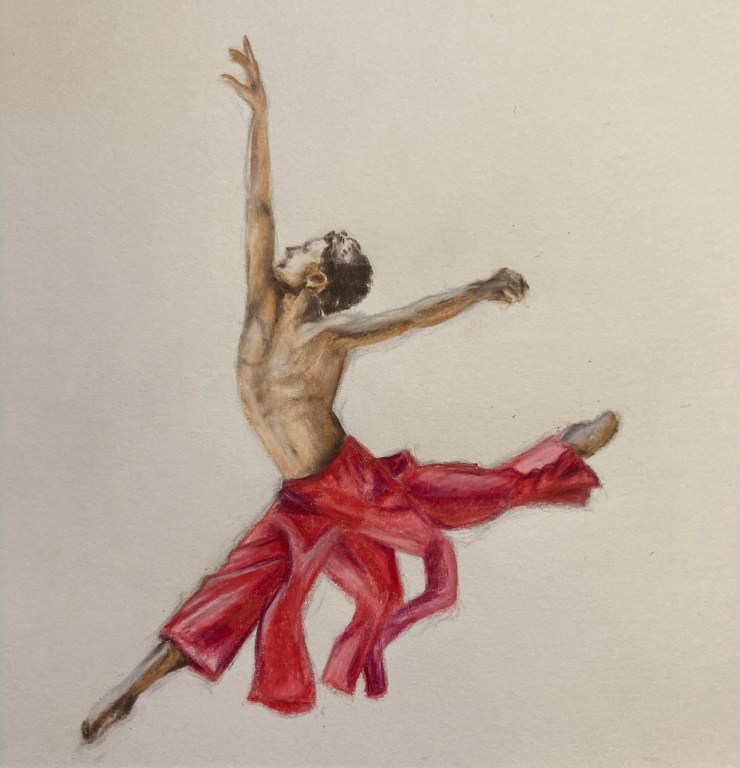

The original 14th Century poem, The Divine Comedy, is divided into three parts: Inferno, where the poet-protagonist explores the nine circles of hell; Purgatorio, where he pines after Beatriz, his deceased childhood sweetheart, and Paradiso, where an angelic adult Beatriz accompanies Dante in a celestial ascent to heaven. Inferno is perhaps the most striking of the acts. McGregor’s tormented, twisting movements convulses through hell’s demonic sinners, who are sprayed with white chalk to represent their crimes – the thieves’ hands are white and Satan appears entirely chalky. Circular patterns in the set and choreography capture the nine circles of hell and represent the never-ending nature of the sinners’ torture – perhaps a nod to the symbolic significance of circles in witchcraft, the demonisation of which was to rip through 1300s Europe.

McGregor’s choreography captures the inhuman in ballet, and Watson is his ideal vehicle. Watson’s gaunt features and signature extraordinary flexibility have engendered a career of unconventional and ambitious roles, including his slime-covered portrayal of the insect in the Royal Opera House’s 2011 production of Kafka’s Metamorphosis. Adès’s score compounds the ballet’s insistent sense of unsettlement as it grotesquely parodies Tchaikovsky’s Land of the Sweets from The Nutcracker, accentuating the onstage mayhem.

Purgatorio brings a sense of stasis after the frenetic first act. Dean’s sketch of a green Jacaranda tree forms a calming backdrop, though we soon see that the souls trapped here are no more at peace than the frenzied miscreants of Inferno. The choreography blurs into the abstract and there is less to hold onto than in the first act, but the newly introduced colours and sounds wash over the audience in sensorial serenity.

Perhaps the eeriest part of the whole production is Adès’s use of recorded liturgical pre-dawn songs from the Adès Synagogue in Jerusalem. Guttural voices cry over the orchestra and meld with the dancers’ looping movements; voice and body combine mesmerically, evoking the purgatorial eternal. The audience reaction is visceral: the sequence feels raw, spiritual and honestly human.

Dean projects a glowing orb of 35mm cinema film at the top of the set in the transcending final act. The orb pulses in kaleidoscopic colours: green, red, white and dazzling gold. Sarah Lamb’s Beatriz wafts in shimmering white underneath, and the audience is torn tantalisingly between the celestial dancers and the glowing ball. The effect is hypnotic. Paradiso reaches an awe-inspiring climax as the colourful film rotates upwards suddenly, emitting a bright, blinding white light. Dante and the audience are momentarily engulfed by heaven.